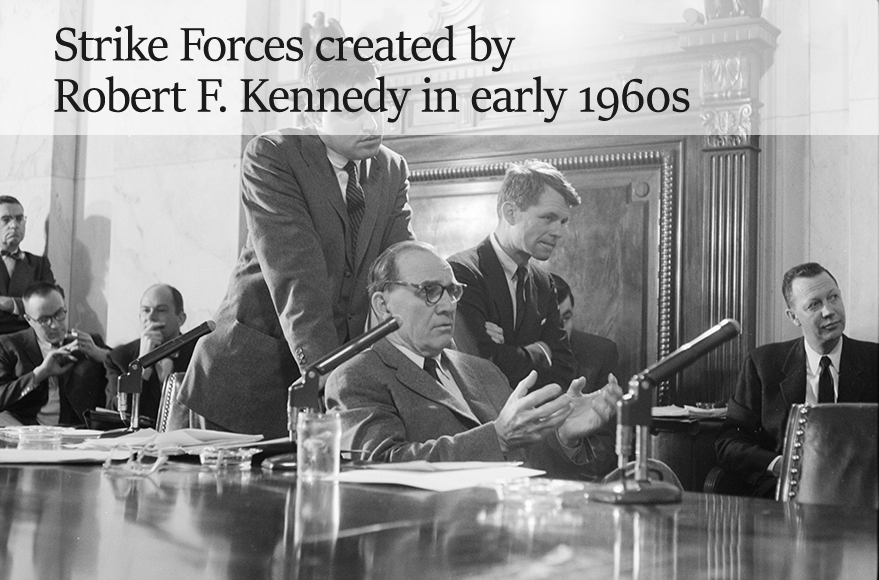

Organized crime strike forces operated by the U.S. Department of Justice across the country from 1963 through 1989.

Today’s column deals with the organized crime strike forces operated by the U.S. Department of Justice across the country from 1963 through 1989.

The strike force program was a national effort to fight organized crime in the United States. It was a program run by the Organized Crime and Racketeering Section of the Criminal Division of the Department of Justice in Washington, D.C. It was perhaps the largest nationwide effort ever operated by the criminal division. There were strike force offices established in Buffalo, Detroit, Brooklyn, Philadelphia, Chicago, Newark, Miami, Boston, New York City (N.Y.), Cleveland, Los Angeles, St Louis, New Orleans, Pittsburgh, Baltimore, San Francisco, Kansas City, and Strike Force18, located in Washington, D.C. I first served on the Chicago strike force, and later was the Attorney in Charge of the Philadelphia and Chicago strike forces.

The concept was simple, to establish offices in key cities where key agents from the various federal law enforcement agencies would be stationed, and who would then exchange information from ongoing investigations and pursue combined efforts as common goals of the Department of Justice prosecutors.

The program might sound simple to the American public; but, in reality, it was a big step in the operation of the criminal investigation agencies of the federal government. There was a saying among career government employees, “the last time there was any semblance of major cooperation between federal government agencies was World War II.”

In the daily operation of federal agencies, federal agents often did not refer investigative leads pertaining to another agency’s jurisdiction. For example, there was a common suspicion among other investigative agencies that the FBI would not pass information pertaining to possible criminal violations in the jurisdiction of other agencies if it would reveal the FBI’s own sources.

The strike force concept was that different agents working together would combine their information to make cases. FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover would not agree to have his agents working in a separate office with other agents. Despite this policy, strike force lawyers worked with FBI agents to make valuable cases. In my own experience in the Chicago strike force, the FBI did not have an office within the strike force office, but the same FBI agents would appear daily at the Strike Force office and meet other agents and attorneys.

When the FBI passed information regarding another agency’s jurisdiction, if an indictment resulted, prosecutors would attempt to include one charge over which the FBI had investigative jurisdiction so that Hoover could claim credit. This is an example of the cooperation practiced by the attorneys and investigators of the strike force.

Strike force attorneys would appear in more than one federal jurisdiction in their territory, thus requiring that they develop the diplomatic courtroom skill to appear before federal judges who did not know them. This is a valuable skill that is necessary to a national effort. Strike force attorneys became very skilled at this practice and over time were well received in the many jurisdictions where they appeared.

The strike forces were created to concentrate on organized crime and were located where the Department of Justice believed were the centers of the organized crime influence. Note that FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover did not believe the local mafia families were a federal problem. This proved to be grossly incorrect. In addition, local police forces did not have the resources nor the expertise to apply sophisticated investigations. It was discovered that many local police forces were corrupted by the mafia. When Hoover died in 1972, his successors in the FBI and the Organized Crime Section of the Department of Justice, made organized crime a national priority.

Major investigations and convictions in the strike force program were the result of the passage of the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (The RICO Act), the Witness Protection, and the Wiretapping Act. The organized crime effort by the government could not have been as successful without these legislative acts.

One of the areas that proved the strike forces’ value was their investigation and indictments in the labor union area. Labor racketeering became a specific targeted criminal activity. This was a particular sensitive area as most powerful labor leaders were politically active and had allies in the Congress and could bring political pressure on the Department of Justice. I recall one incident in Chicago when we are going to file charges against several very prominent labor leaders who were leaders in the Democratic party of Cook County. I presented my charges to the U.S. Attorney, who was a powerful figure in the Democratic party, and explained he would hear from the party. He advised that I should file the charges, and he would handle any pressure from them. His career successfully continued after he left the U.S. Attorney’s Office.

The strike forces were highly successful. Good prosecutors were trained in those units, and many went on to become leaders of Criminal Division. I became the U.S. Attorney in Philadelphia in both the Carter and Reagan administrations.

The Department of Justice, as any government agency, needs to prove it is needed to continue. As time passed, the Department of Justice found other areas that needed special attention. Drug rings became a national concern. Curiously, organized crime families did not participate in drug sales or distribution. Investigation of organized crime families no longer was a national concern. The Labor Department, once a regulatory type of agency, created a labor racketeering unit with specially trained investigators. The U.S. Attorney’s Offices trained more of its Assistant U.S. Attorneys in labor racketeering. The strike forces were merged into the U.S. Attorney’s Offices in1989. Their mandates were changed to include other specific areas of inquiry. In the Reagan administration, the Department of Justice directed that Assistant U.S. Attorneys were no longer political appointments and could not be removed upon a change of administration.

The Department of Justice deserves credit for its creation of the strike forces and the expertise obtained by its members. The strike forces exposed the need for prosecution of labor racketeering. There is now an expertise of federal prosecutors across the country in labor racketeering. I owe my former career in the Department of Justice to my time in the Strike Forces.

Peter Vaira is a member of Weir LLP. He is a former U.S. attorney and the author of a book on Eastern District practice. He acts as special hearing master for Pennsylvania courts and clients.

Photo: By Marion S. Trikosko – Public Domain

This article is reprinted with permission from the November 11, 2025 issue of The Legal Intelligencer. ©2025 ALM Media Properties, LLC. Further duplication without permission is prohibited. All rights reserved.